“A writer needs friends who simply benefit from knowing him, which is another way of saying that good writers need good readers. And just as writers need to work at it to write well, so also readers should work at it in order to be able to read well. My hope in this book of introduction is to help us all become better readers of some fine writers.”[1]

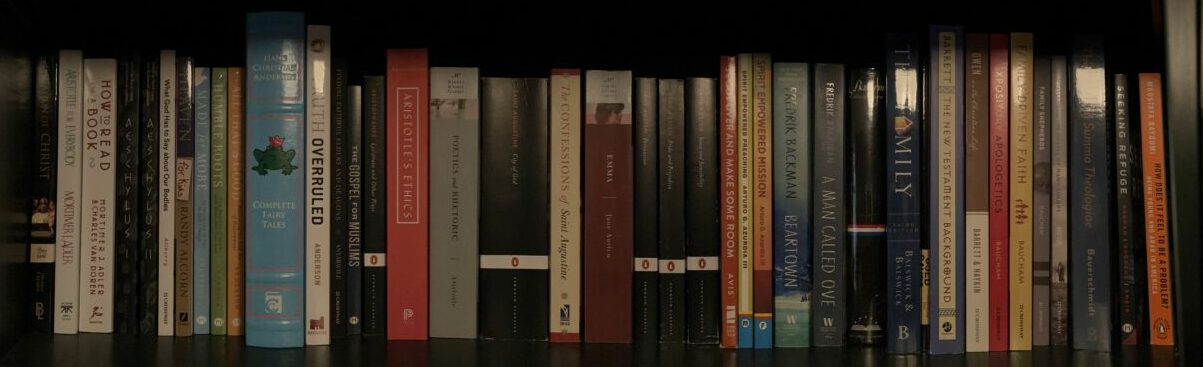

As you might have noticed, I have been reading quite a few books from Doug Wilson. He is an interesting writer and I often enjoy his takes, whether I agree with them or not. This is also a quality that I appreciate about Wilson. He doesn’t have to agree with you to engage with you in the realm of ideas. Evidence of this is the Writers to Read: Nine Names That Belong on Your Bookshelf. These nine writers are as follows: G. K. Chesterton, H. L. Mencken, P. G. Wodehouse, T. S. Eliot, J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, R. F. Capon, M. S. Robinson, and N. D. Wilson.

My assumption is that you’ll take a look at that list and know a few favorites, but not have a clue about a lot of them. That was my situation. Other than Lewis and Tolkien, I have not read much of any of the other authors. Thus, it was helpful to read through this book and get insights as to why I should.

What You Need to Know

Wilson begins each chapter with some biographical information and then moves into why that specific author is important to read. At the end of each chapter, he outlines the books that he would read and also which ones he would begin with.

It is quite clear that he has his favorites. Chesterton, Tolkien, and Lewis are definitely his favorites. Lewis is probably chief of the three, which surprised me for whatever reason. It should also be noted that not all of the authors are Christians. With each author, Wilson connects him/her to the Christian religion through a person or his/her faith connection. However, that is helpful to know before you go in to read.

Lastly, the final author that Wilson mentions is his son, N. D. Wilson. He discusses the rationality for including him, but then moves on. The chapter isn’t bad. It provides a different sort of insight. I appreciated it for getting a picture into Wilson’s family and hearing about the life choices they had to work out as a family. Since N. D. Wilson had almost exclusively written young adult or children books, I will probably only read him with my kids, if I ever do.

What I Want You to Know

Wilson’s chapter on C. S. Lewis is good. It provides a deeper look into Lewis than I had previously experienced. For example, he cites a book called Planet Narnia, which argues that each of the Narnia books has a “planetary” connection. The Silver Chair is connected to the moon. The Last Battle is connected with Saturn. The Horse and His Boy is connected to Mercury. It is quite compelling and I am trying to work through the Narnia books now because of it.

Like the book Planet Narnia, Wilson provides a lot of good books to consider. Most of these are for the nine specific authors, but that is not solely the case. As someone who enjoys getting new books, that worked well for me. I actually purchased a book for my wife’s birthday from one of the chapters.

Furthermore, I appreciated that the focus on each of the authors was about his/her strengths. For example, Wilson considers P. G. Wodehouse as one of the greatest authors in regards to the metaphor. He remarks, “Simply put, Wodehouse is a black-belt metaphor ninja… The metaphors are consistently laugh-out-loud funny, but they are more than that. They are arresting. They are memorable. They connect things that are not usually connected. They show wordsmiths how wordsmithing needs to be done, but they also help ordinary folks liven up the discourse of their lives.”[2] He gets even more complementary, but I’ll stop there. Wilson argues that loving metaphor is important for the Christian: “Ultimately, I believe that Christians should love metaphor because we are servants of the Logos, the Word. The Word was with God, the Word was God, the Word became flesh. What we have here is the basic foundation for a theology of metaphor. We have distinction, we have identification, and we have incarnation.”[3]

Wilson doesn’t allow a sacred and secular divide, but shows the importance of something as particular as a metaphor for the Christian life. This is something I would like to do better myself; thus, I have been reading more of Wilson.

How I Scored It

My scoring system is made up of a 5-point scale for writing, content, enjoyment, and re-readability with weighting 20 percent, 15 percent, 40 percent, and 25 percent, respectively. (Please debate me on this if you are so inclined.)

I am not sure that I will be re-reading it any time soon, although it is likely I will reference it as I plan on reading some Wodehouse, Chesterton, and Robinson. Not to mention, I have already ordered C. S. Lewis’s The Discarded Image. Wilson did a good job of getting me excited for some of those authors.

How About a Taste

“If words are weapons—and they are—then we need to train ourselves in the use of them. It is quite possible that a novice doesn’t see the connection between this particular swordplay drill and what he could do in an actual battle, but he doesn’t see this because he is the novice. An ability to respond on the spot with a bon mot is winsome. And as D. L. Moody once put it, if you are winsome than you win some.”[4]

“Lewis was an imaginative genius. But more than that, he was a man who understood that a rightly ordered imagination was a fortress for the rational capacities of man. It is easy to think that clearheadedness is the fortress and that it protects the imagination, what we are allowed to play with in our recreational hours. But Lewis’s tough-mindedness was the result of having been given a sanctified imagination. In the apostle Paul we see the same kind of thing—it is the peace of God that passes understanding that protects our ‘hearts and … minds’ (Phil. 4:7). It is not the other way around. One of the reasons many apologists are not nearly as effective as Lewis is that they want the cold granite of reason to do everything. But true reason will collapse before a false imagination. False imagination must be answered by a true imagination, and when that happens, reason can flourish in its native habitat.”[5]

[1] Douglas Wilson, Writers to Read: Nine Names That Belong on Your Bookshelf (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2015), 12.

[2] Ibid., 51.

[3] Ibid., 52.

[4] Ibid., 55.

[5] Ibid., 105.